Critically establishing a text

1. Establishing the text

Most premodern Chinese texts have been transmitted as woodblock prints, but these texts have no punctuation in the modern sense. Many texts are interspersed with one or more commentaries. The preparation of these texts into the line-based format used to occur outside of the database as a preparatory step. In order to bring this important research activity within the realm of the collaborative work, and to allow also partially established texts to be annotated and translated, some new procedures have been added.

It has now become possible to extend the workflow and bring the editorial task of establishing the text, add punctuation to mark phrases, into the system. After a phrase in the text has been established, this section becomes available for annotation and translation.

2. Text-critical editing within the TLS

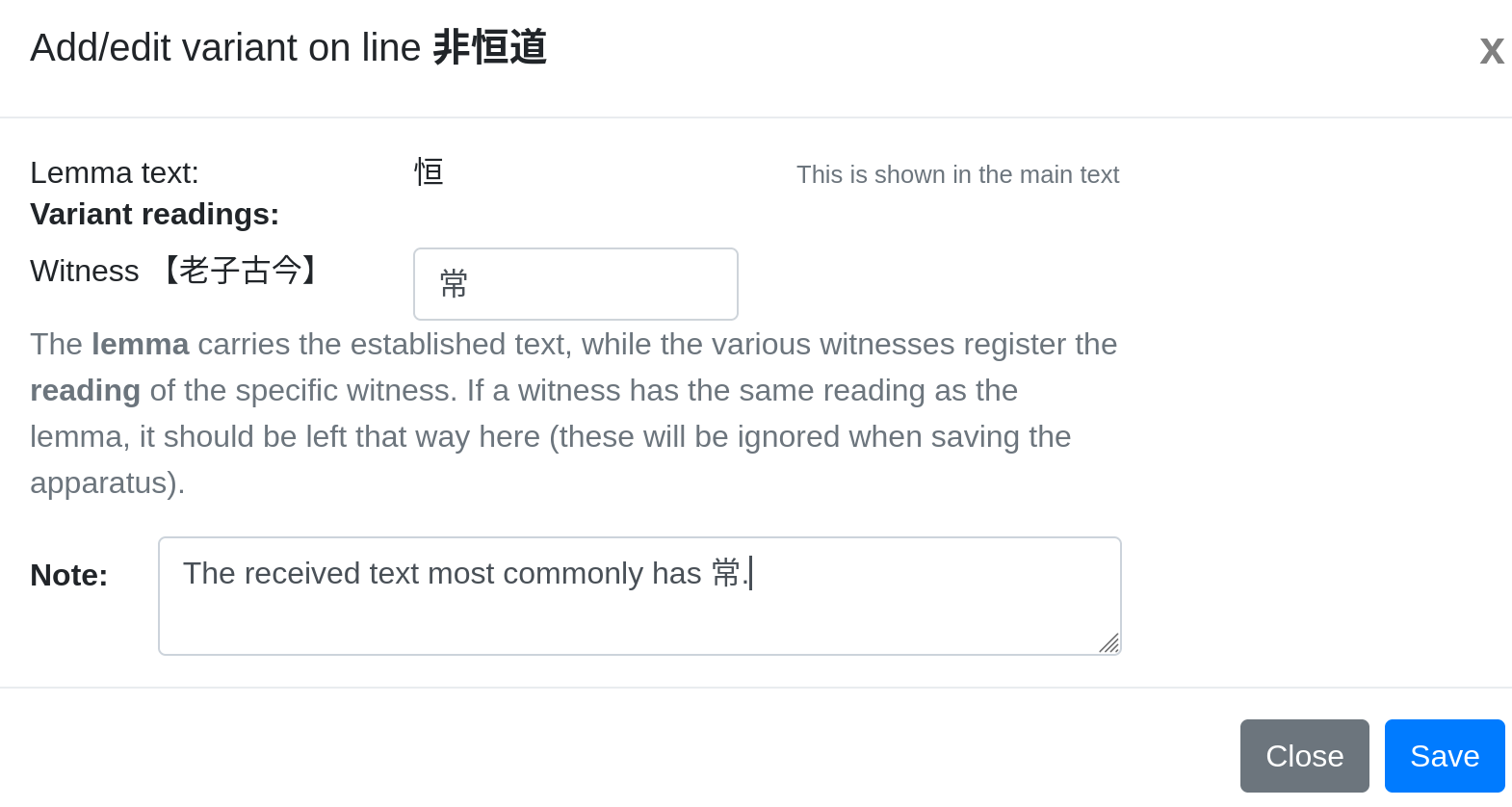

The HXWD website supports a simple workflow for recording variant readings for different editions of a text. These variant readings are stored as apparatus entry according to the recommendations by the TEI Guidelines, using the 'double-end-point' method (see 12.2.2 The Double End-Point Attachment Method) attached externally. This allows full reconstruction of the text of every witness.

To enable text critical editing, some prerequisites must be fulfilled. First of all, a list of editions to be considered for the apparatus needs to be provided. The system will require that the editions are added to the bibliography and subsequently linked to the text for which they provide a witness.

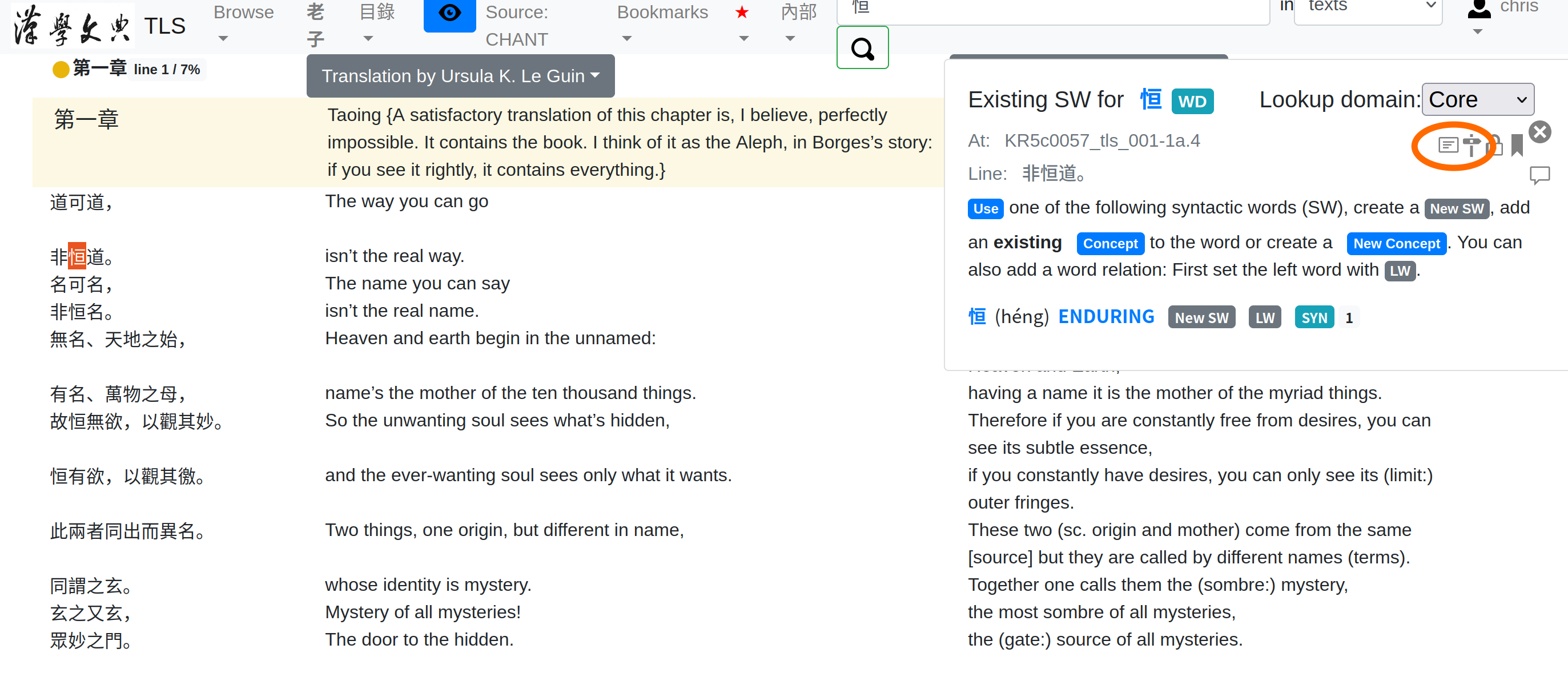

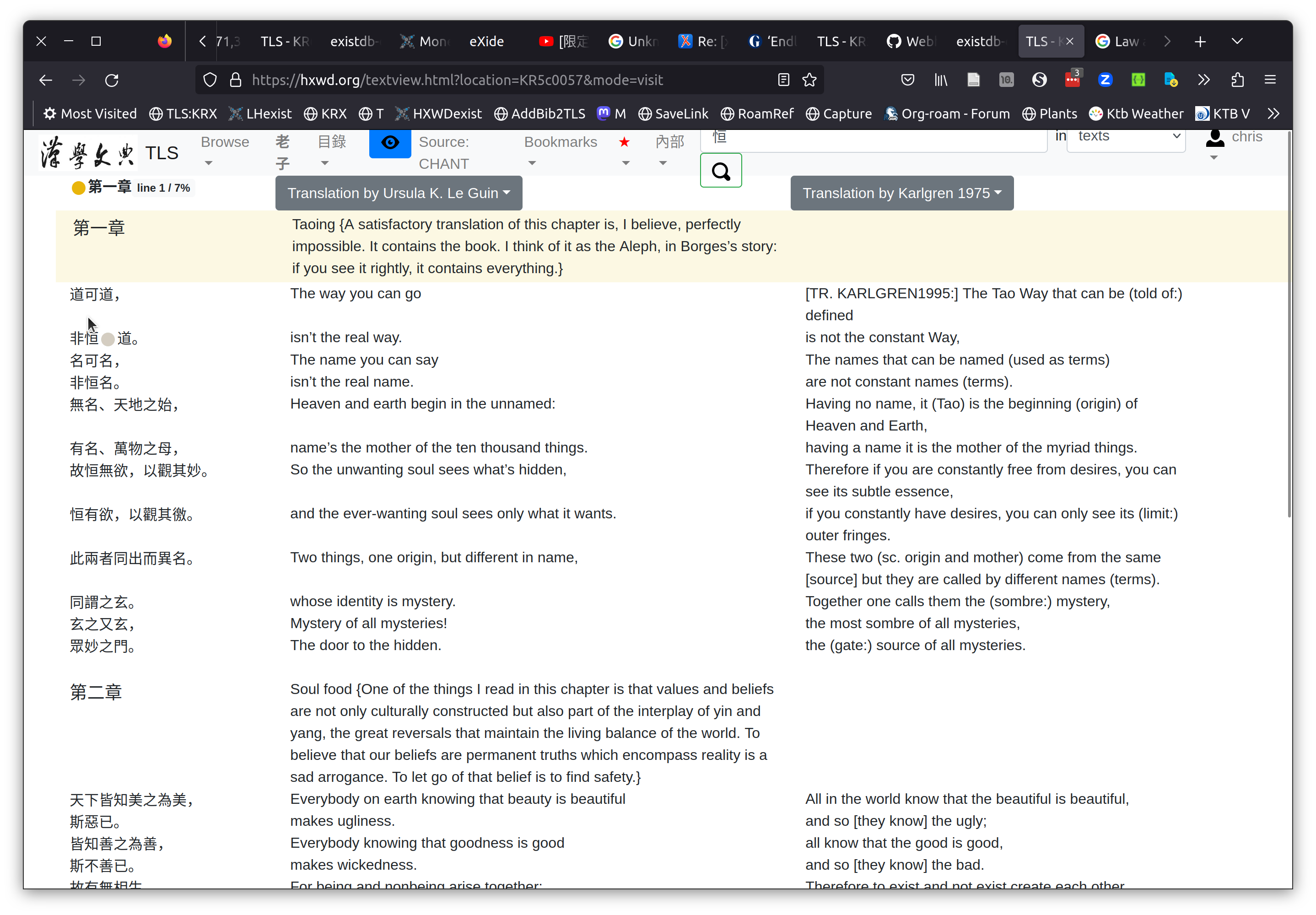

Figure 1: Floater on Laozi 1, with 恆 selected.

There are several ways to add the witnesses. The most obvious and easiest to reach one is available from the floater. There are two buttons available for those with permission to do editing on texts, in Figure 1 they are shown in the orange circle. The leftmost of these, with an icon simulating text lines, is used to access the apparatus editing. It will act on the currently selected line and string of characters. The other button to the right of this is used to indicate page breaks, this also requires textual witnesses to be defined. If no witnesses are defined, either of them will produce a message similar to the one shown in Figure 2.

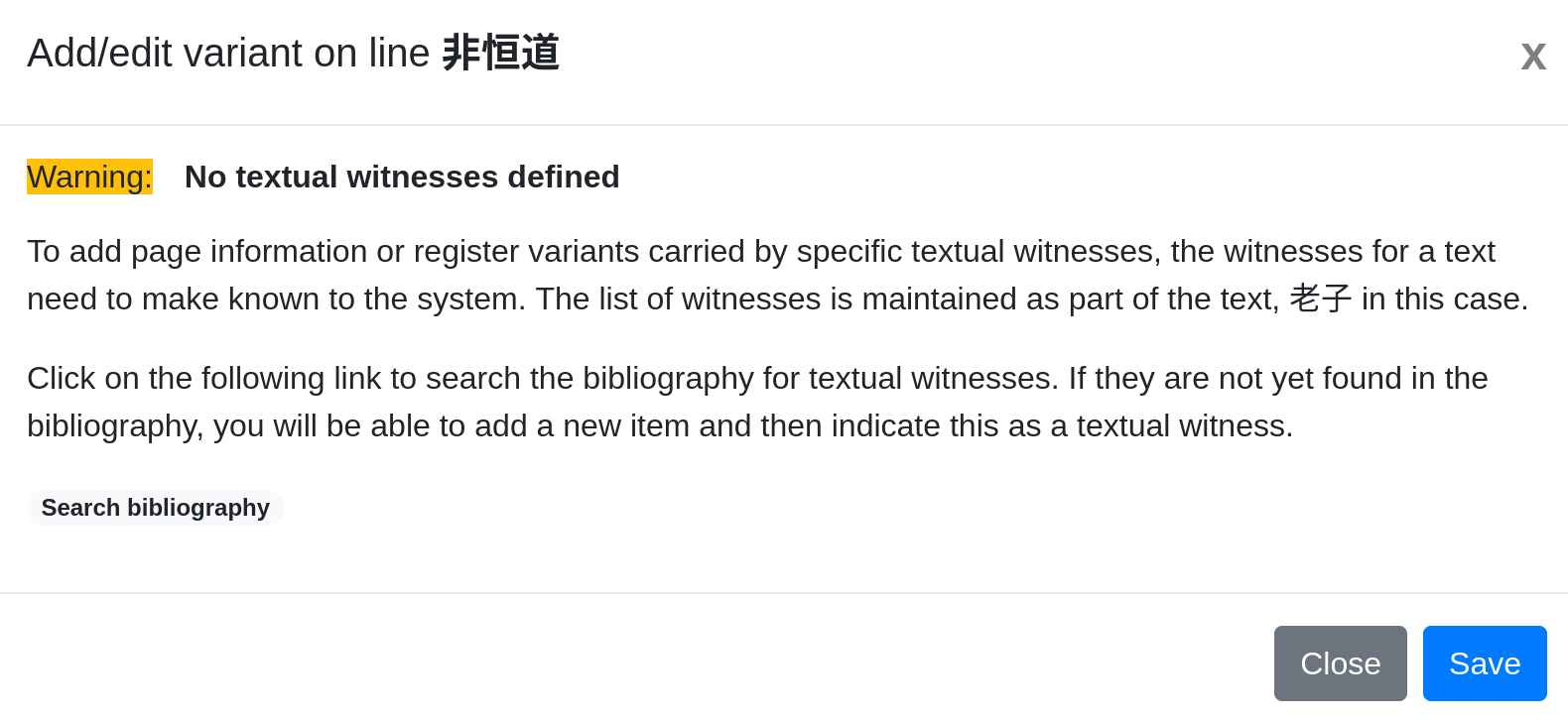

Figure 2: Warning shown when no witnesses are available

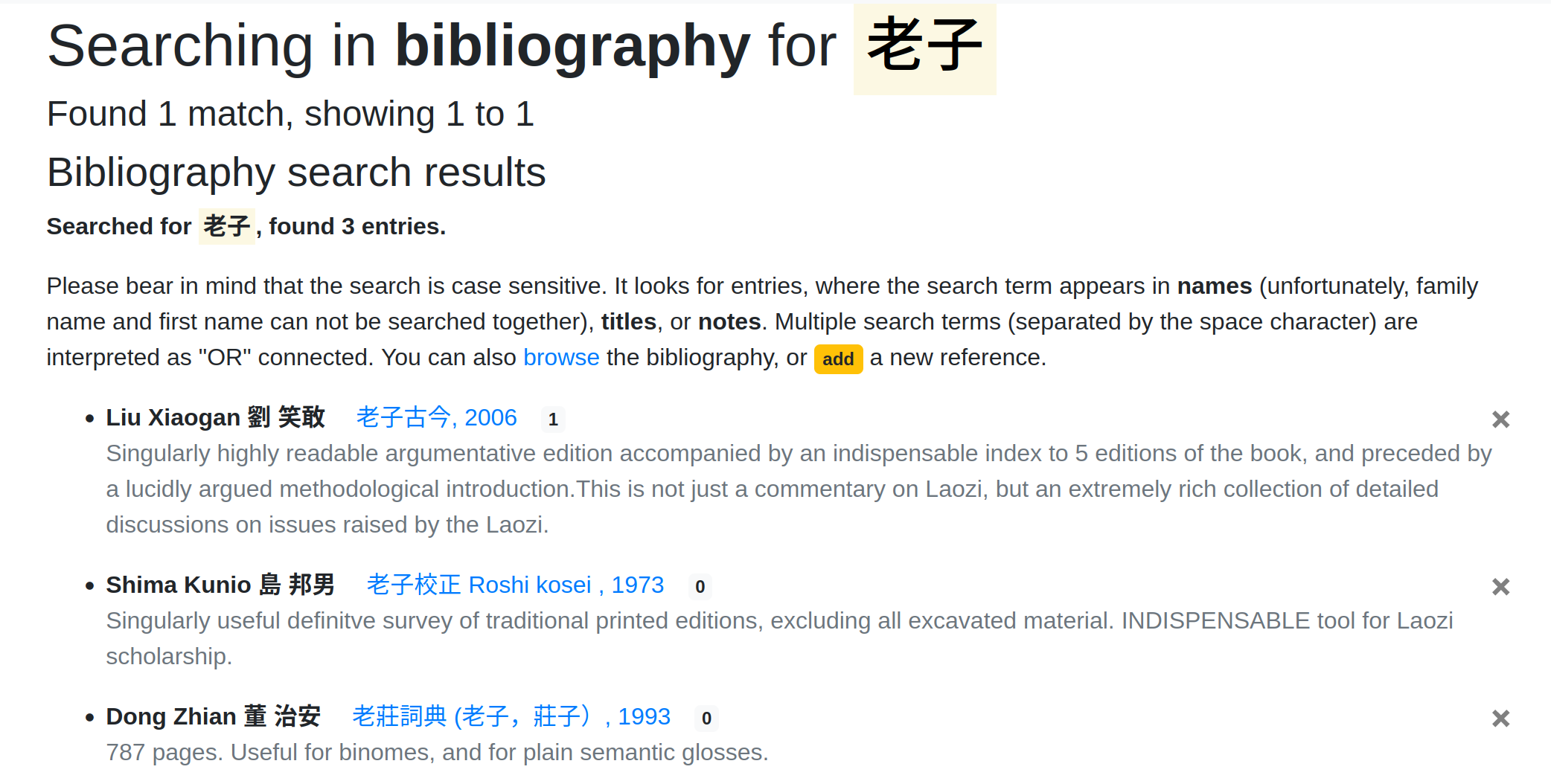

In order to proceed, we need to add the witnesses to the bibliography. Helpfully, there is a link, which we can use to start this process. It will simply search for the title of the text in the bibliography, in the hope that this might show something useful. Figure 3 shows an example of how this might look. If yes, we can click on the title of the bibliographical item and look at the details, on this screen, there is a button that allows editing of this item. The editing screen will provide a way to link the bibliographical item as witness to the text.

If the witness is not yet registered in the bibliography, we can immediately add a new item and link it to the text as witness, by clicking on the yellow 'add' a new reference button.

Figure 3: Search results for 老子 in bibliography

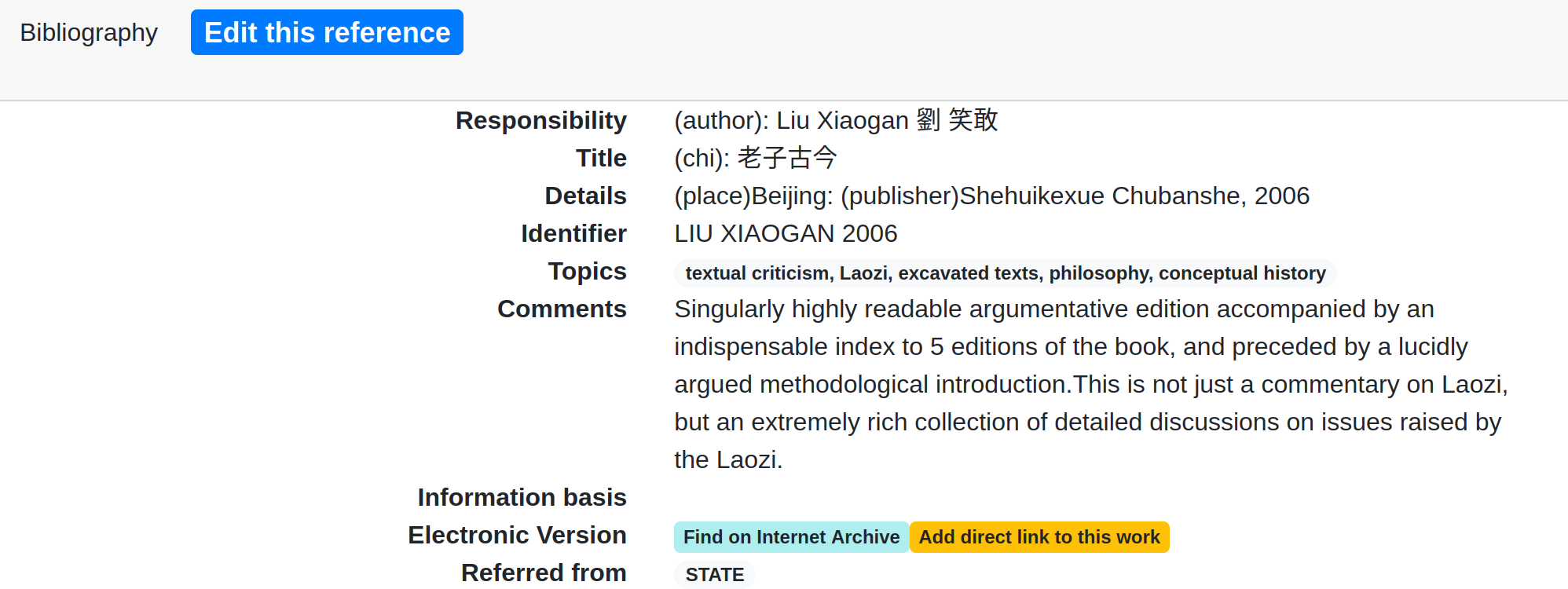

Figure 4: Details for Liu Xiaogan 劉笑敢: 老子古今

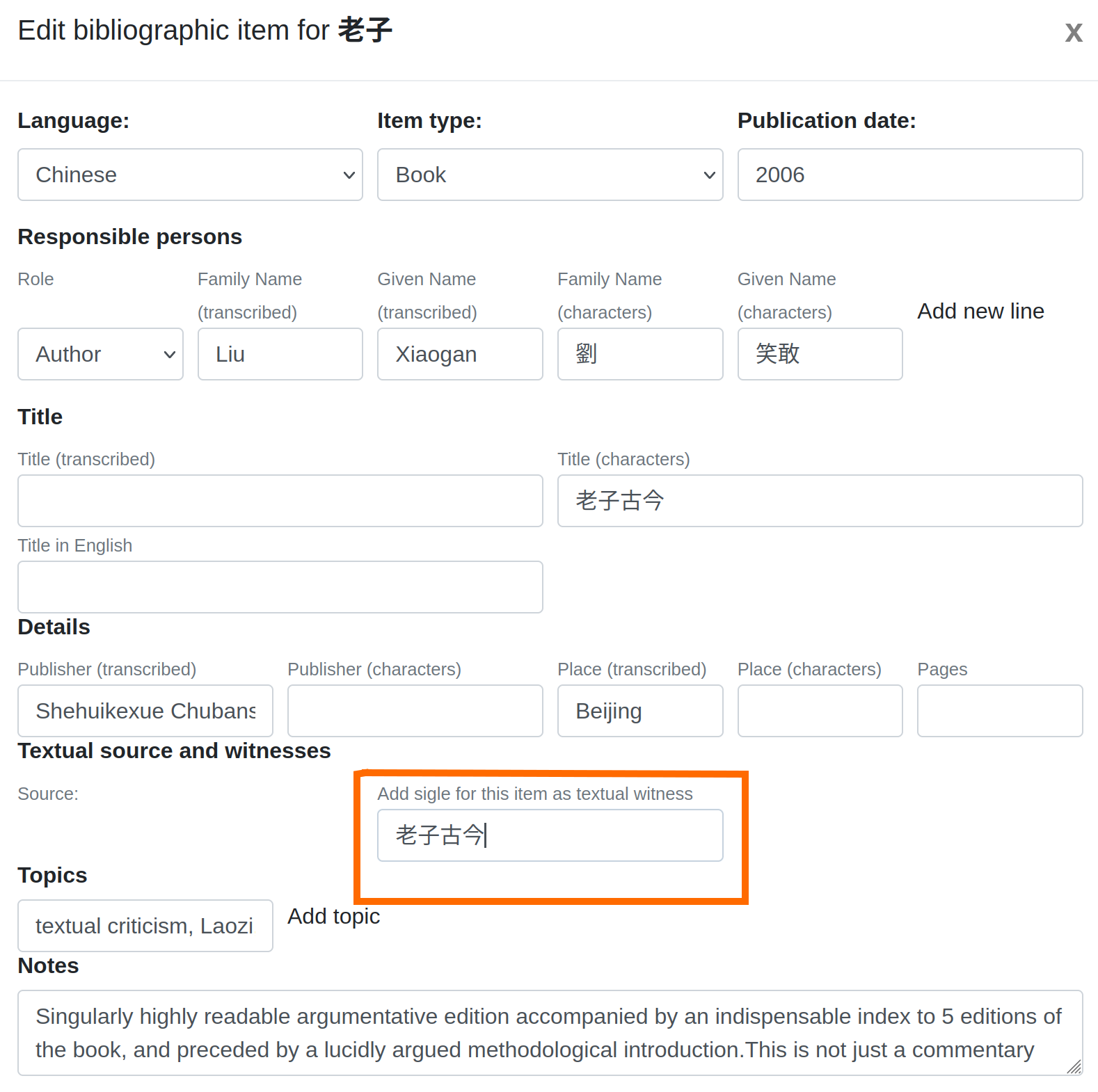

Figure 4 shows the details for the item on Liu Xiaogans 劉笑敢 Laozi Gujin 老子古今. A click on the bib blue button 'Edit this reference' will open the edit dialog for this entry, with all the available information already filled in. In the screen shown in 5 in the lower part (indicated by the orange rectangle), a sigle has been added for this text. The presence of a sigle here will tell the system that this bibliographical item should be linked to the text indicated (as in the title of this screen, which says 'Edit bibliographic item for 老子') text.

Important: The input for a sigle is only available when the search in the bibliography has been initiated from the text view as in our example.

A sigle can be arbitrarily chosen, it will be a shorthand within the system to refer to this item in its function as witness, so it should be meaningful at least in the context of the text under revision.

Figure 5: Editing item for Liu Xiaogan 劉笑敢: 老子古今

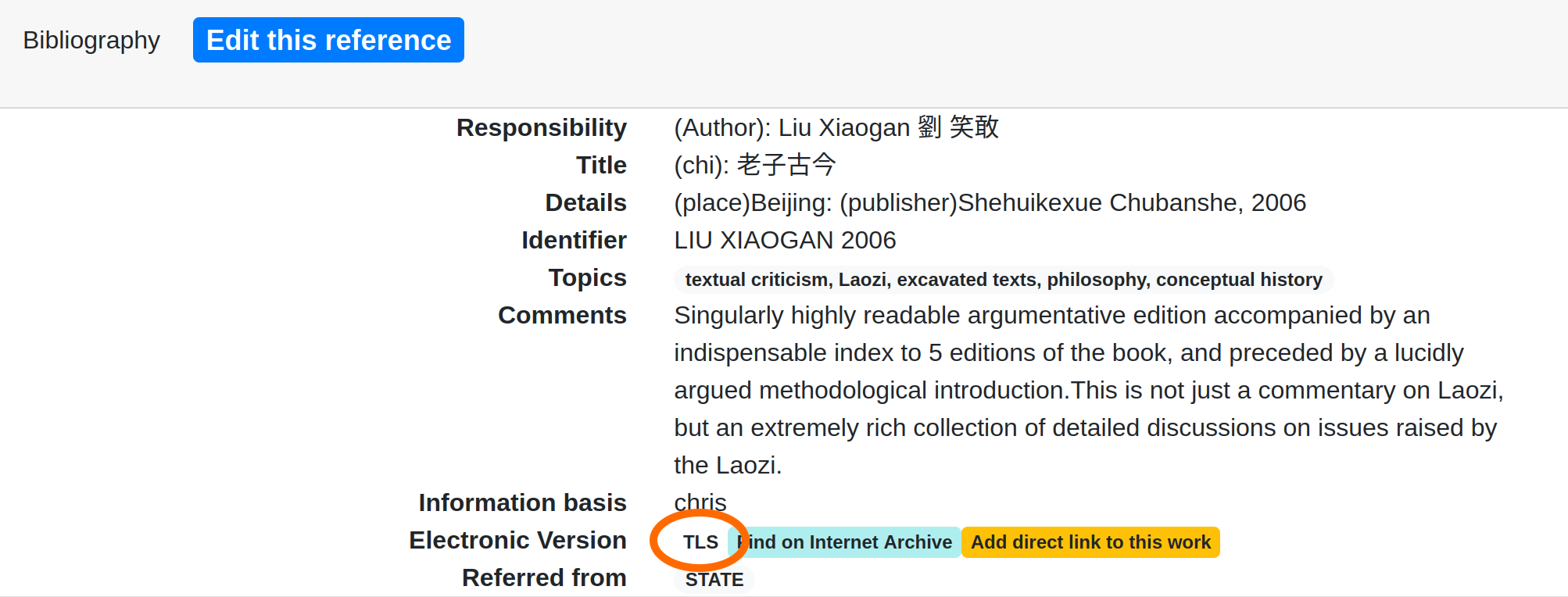

Figure 6: Details for Liu Xiaogan 劉笑敢: 老子古今, again

Figure 6 shows the result of the editing, on this screen the only change is that a link to the text within the TLS has been added to the section 'Electronic Version', again indicated in orange on this screen.

If we click on that link, it will bring us back to the text, to the location we just visited. We can now click again on the leftmost button of Figure 1 and, since we now have at least one witness in place, we will see a screen similar to Figure 7

Figure 7: Variant editing in Laozi 1

Figure 8: Text display with indicator for variant reading

And finally, after saving the apparatus, after refreshing the page, we will see the new apparatus entry, as it is indicated in the copy text with a grey circle, similar to 8. The screenshot unfortunately does not show that moving the mouse over the circle will show the exact nature of the variant.

3. Translating

Strongly connected to the task of close reading, the TLS offers to immediately add a translation to any line for which the text has been established.

Translations are maintained as parallel text, aligned with the source text. Translations can be fragmentary, but ideally operate on the same phrase as the source text. Any number of translations in any language can be added to the system. To help with translation (and annotation), existing attributions can be inspected at any time. In the same way as translations, research notes or commentary can be attached to text lines.